Angola’s past is defined by centuries of foreign rule and forty years of constant war. The story begins in 1482 when Diogo Cão anchored a Portuguese fleet at the mouth of the Congo River. This arrival started a slow creep of European religion and culture that hardened in 1575 with the founding of a trading post in Luanda. That settlement became the anchor for total control over the territory. The Angolan people waited nearly four centuries to demand their freedom and in 1961 they launched the War of Independence, a conflict that burned until 1974. That same year, the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon, Portugal, toppled the dictatorship of Salazar and Caetano, finally breaking the colonial grip.

Independence came in 1975 through the Alvor Agreement, but it brought no peace. The country immediately fell into a brutal Civil War that did not end until 2002. Through all this violence and into the present day, the people have lived under the single, continuous rule of the MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola).

“We want to bring to Angola a variant of rock that connects us and at the same time separates us from everything we know, to be a scar inside the hearts and minds of any person who hears and sees what we have been doing.”

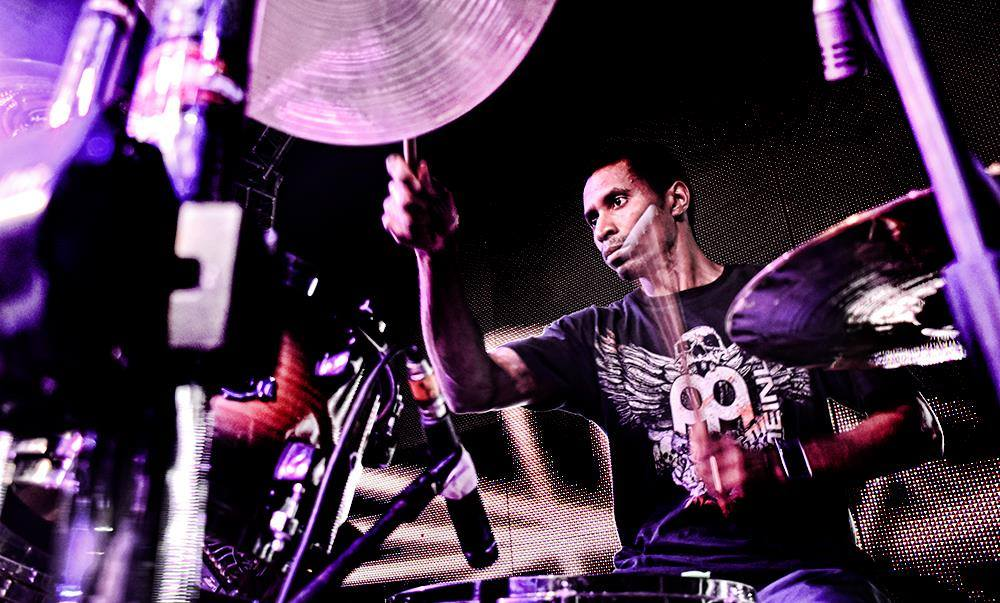

In a nation famous for the rhythms of kizomba and kuduro, rock music seems like an outsider. Yet the genre has survived here since the 1960s, documented in independent films and kept alive by a small circle of devotees. Yannick Merino, drummer for the black metal band Horde of Silence, explains that heavy music is not new here: “The rock style has existed in Angola since the 1960s, while the metal subgenre appeared in the 1990s through television and some people who lived outside Angola and brought music to show the guys,” Merino says. Henriques Chitumba, bassist and vocalist for the thrash metal band Dor Fantasma, agrees. He points out that while metal remains underground, its foundations were laid before the fighting even stopped: “In Angola, rock/metal has never been and is still not a style totally accepted and consumed by a large number of people. The genre was already inserted in the Angolan musical landscape before the civil war through musicians who mixed blues with traditional Angolan rhythms, but it was from the 1990s that a greater openness emerged for access to extreme songs, and many of them kept opening our musical horizon until we familiarized ourselves with metal and defended the concept.”

For Merino and his friends, discovery came through any channel they could find. They traded music with acquaintances, watched television during the golden era of music videos, and eventually logged onto the internet: “When MTV was really a music channel [laughs],” Merino jokes. He notes that the shift to heavier sounds happened naturally over time. “We all started with other bands and over time we started to appreciate heavier styles more and more; when we realized it, we were already listening to and playing extreme metal.”

For these musicians, the music is a physical necessity: “We like the style because it is an aggressive, fast and technical sound,” Merino says. “It unleashes the animal inside us that has been imprisoned for so long, yearning to break free.”

The scene is incredibly small. A search on the Metal-Archives database shows only seven active bands in the entire country. This scarcity speaks to the massive difficulty of being a rock musician in Luanda or Benguela. Merino identifies the lack of studio knowledge as the primary barrier: “Recording a metal record in Angola is extremely complicated, as there are no rock producers,” Merino admits. He estimates that “99.9% [of producers] are focused on semba, kizomba, rebita, rap and hip-hop.” This forces the band to take charge of the technical process. “When we go to record we still have to ‘teach’ the producers what they must do.”

For Chitumba, the problem is distance. Finding a studio that can handle their sound means traveling hundreds of kilometers, a logistical nightmare for people with day jobs: “The biggest and main difficulty in getting a high-quality digital recording has been accessing the studio that offers the best technical conditions for metal, which is 700km from our city,” Chitumba explains. “And because of our jobs, it has been complicated to coordinate our time off to go record, but little by little we get there and always record something until we finalize our first album.”

Both bands are featured on the split release You Failed… Now We Rule!!! alongside acts like Before Crush, Fiona, and Eternal Return. Getting people to come see this music live is another battle entirely. Chitumba describes the need to perform “mental work on the people who can go see the bands up close, and many for free, but do not go to the concerts.” Despite the empty rooms, Dor Fantasma keeps playing. For Horde of Silence, the challenge is also financial: “Almost nobody sponsors rock, especially in the capital Luanda,” Merino says. The band solves this by paying for everything themselves.

Operating under the long-standing MPLA regime brings its own tensions. Reports of censorship and persecution, such as the case of activist Luaty Beirão, are well known. Merino accepts that choosing this path places them on the fringes of society: “Censorship will always exist,” Merino says, adding that “rock is still not well seen in the eyes of Angolan society.” But he insists their message is positive. They want to “transmit that rock is not only noise” but that it stands for “peace, harmony and love.”

Chitumba shares this hope. He believes the music can eventually change how people treat one another: “The day will arrive when people will wake up and surrender to loving their neighbor and respecting what belongs to others,” Chitumba asserts. He sees their work as a “defense of the democratic question as being an open battlefield” while knowing “that in the world in which we live there exists, and will always exist, a ‘system’ that pollutes minds.”

Regardless of the obstacles, the members of Dor Fantasma are committed to the road: “Our fingers breathe this journey and musical freedom,” Chitumba says. His goal is to leave a permanent mark. “We want to bring to Angola a variant of rock that connects us and at the same time separates us from everything we know, to be a scar inside the hearts and minds of any person who hears and sees what we have been doing.”

The plan now is to build a legacy. Chitumba wants to raise “a generation well prepared to defend the metal concept.” He concludes with simple gratitude. “Being on stage in Angola and around the world will always be a pleasurable experience.” Merino is equally determined, as he sums up the spirit of the scene: “Forward is the way. Despite the obstacles, we want to break all existing barriers.”

Disclaimer: This article was adapted from original interviews conducted by writer Diogo Ferreira for Ultraje magazine (June/July 2018 edition), under the editorship of Joel Costa. Special thanks to Horde of Silence and Dor Fantasma for providing the images.